How Technology Is Shaping The Way We Evaluate Pitchers

How Technology Is Shaping The Way We Evaluate Pitchers

Nate Walker explains what pitchers should know about spin rate, spin efficiency, spin axis and more.

Nate Walker is a former baseball operations employee for two Major League Baseball front offices where he served as a liaison to the Major League coaching staff, assisting them with game preparation, in-game strategy, and statistical research. Nate is currently the Founder and President of Diamond Solutions, an analytics consulting firm that assists softball and baseball organizations with their analytical needs.

Player evaluation has always been an inexact science. Throughout Major League Baseball’s (MLB) history, there have been “can’t miss” prospects who fail to make it past Double-A, and there have been no-name minor leaguers develop into MLB assets, shocking the entire baseball world as they do so. Although it may seem like player evaluation is an impossible job to master, the most successful evaluators, both scouts and statistical analysts, always ask themselves two simple questions when analyzing a player.

What are the player’s strengths and weaknesses and why are these strengths and weaknesses signals of a successful or unsuccessful player?

The first question is relatively straightforward to answer. For instance, Pitcher A has great sink on her dropball. The second question, however, is much more complex, and often leads to more questioning in order to complete an accurate player projection. For example, does Pitcher A’s dropball have enough sink to beat a power hitter’s upward swing trajectory? If not, how does this affect the player’s overall value?

One tool that provides evaluators with clarity on these types of questions is pitch-tracking data. Pitch-tracking data is a powerful tool that exposes every inch of a pitcher’s repertoire, and when incorporated correctly, it greatly improves the accuracy of player evaluation and the overall quality of player development. On May 14th, 2018, I was fortunate enough to collect pitch-tracking data on Delanie Gourley and Danielle O’Toole so I could perform an MLB Front Office type evaluation to analyze why these two pitchers are considered some of softball’s elite.

Pitch Tracking Data Explained

In order to collect the pitch-tracking data for this analysis, we used a piece of radar technology called Rapsodo. After a pitcher throws a pitch, the device calculates the pitch’s velocity, spin rate, spin efficiency, true spin, spin axis, vertical break, and horizontal break. For those unfamiliar with spin data, spin efficiency and true spin measure how much spin is related to actual movement.

Spin efficiency is expressed through a percentage while true spin is the total spin multiplied by the spin efficiency. If a pitch is spinning with complete backspin or topspin, the spin efficiency will be closer to 100%. If a pitch has a spin efficiency of 0%, that means the pitch is spinning completely like a bullet and does not generate any “true” movement.

For this article, we will focus more on spin rate, vertical break, and horizontal break, but spin efficiency and true spin are both very important concepts, especially when developing the shape of a pitch. The major benefit to using pitch-tracking data is it allows analysts the opportunity to find correlations between movement/spin combinations and specific results (i.e., high spin pitchers generate more fly balls than low spin pitchers).

Once the analyst identifies the correlations, he/she can then determine which movement/spin combinations generate the best results. If an evaluator can identify the optimal movement/spin combinations and supplement that knowledge with high-quality subjective reasoning, he/she will be in a substantially better position to accurately project the player’s future value.

Identifying a Pitcher’s Analytical Profile

When analyzing pitch-tracking data, the first step is to classify the pitcher’s analytical profile. To do so, we will look at the tables below which reveal the median values of each pitcher’s velocity, spin rate, vertical break and horizontal break data. For the vertical break row, a negative number represents a sinking pitch while a positive number represents a rising pitch.

A rising pitch does not mean the pitch is technically rising, rather, it means the pitch is defying gravity and holding its trajectory longer than a sinking pitch would.

For the horizontal break row, a negative number represents an arm-side break for a left-handed pitcher while a positive number represents glove-side break. Please keep in mind that we tracked these numbers for a video production, therefore, their velocities will not be as high as what they typically throw in a game.

Delanie Gourley (LHP)

| Metric | Fastball | Riseball | Dropball | Curveball | Off-Speed | Changeup |

| Velocity (MPH) | 61.9 | 62.2 | 61.6 | 63 | 55.8 | 51.4 |

| Spin Rate (RPM) | 1415 | 1595 | 1565 | 1571 | 1395 | 1330 |

| Vertical Break (Inches) | -0.1 | 2.3 | -2.5 | 0.7 | -3.9 | -2.2 |

| Horizontal Break (Inches) | 3.9 | 4 | 4 | 1.4 | -5.1 | 4.7 |

When analyzing the charts, it is clear that Gourley and O’Toole are two completely different pitchers. Gourley is a high spin pitcher that generates a large amount of horizontal movement while O’Toole is a low spin pitcher that can create a significant vertical separation between her sinking and rising pitches.

The overall goal of identifying a pitcher’s analytical profile is to provide an evaluator with an objective snapshot that explains how a pitcher gets a hitter out so that he/she has a proper starting point to evaluate the pitcher’s strengths and weaknesses. After the evaluator classifies the pitcher’s analytical profile, the next step is to analyze how a pitcher’s pitches move in relation to one another and then determine if the movement/spin combinations will dominate advanced hitters. The best way to answer this question is by using one of the most popular tools in an MLB Front Office, the pitch movement chart.

Movement Charts Explained

Pitch movement charts are an extremely useful tool because it provides the evaluator with a snapshot of the pitch’s total and relative movement. Before I break down Gourley’s and O’Toole’s movement charts, it is important to explain how to interpret a movement chart.

The Y-axis (vertical) represents vertical movement. Any dot in the negative region is considered a sinking pitch while any dot in the positive region is considered a rising pitch. Any dot in the negative region on the X-axis (horizontal) shows a pitch has glove-side break for a right-handed pitcher, arm-side break for a left-handed pitcher while any dot in the positive region on the X-axis shows a pitch has arm-side break for a right-handed pitcher, glove-side break for a left-handed pitcher.

When you see a chart of a Major League pitcher, the horizontal break descriptions are the opposite of a softball chart (i.e., a dot in the positive region is glove-side break for a right-handed pitcher, arm-side break for a left-handed pitcher). The overall goal of analyzing a pitch movement chart is to identify optimal movement combinations.

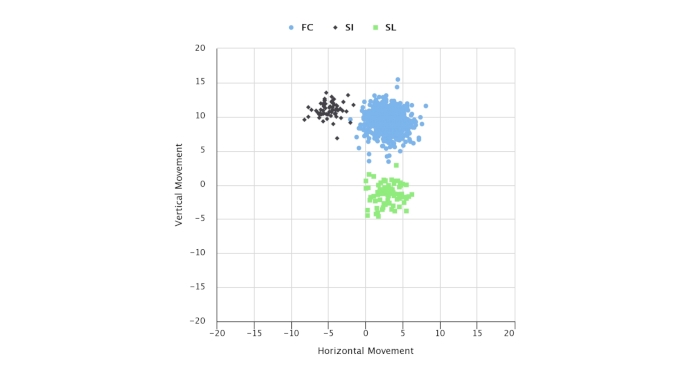

An optimal movement combination is a combination of horizontal and vertical movement that increases the probability of a swinging strike or weak contact. It would take an entirely separate article to explain what qualifies as an optimal movement combination, so to keep this explanation brief, I will show you the poster boy of optimal movement, Clayton Kershaw.

If you look at the chart above (taken from fangraphs.com), you should notice that Kershaw has three sets of dots stacked on top of one another. What this means is he has three pitches with very similar horizontal movements, yet three distinctly different vertical movements, including plus vertical separation between his fastball and curveball. If a pitcher can throw three different pitches that all come off a similar horizontal plane, the hitter will have difficulty identifying the pitch early in its flight. Kershaw is one of the best at this, and his movement profile is a big reason why he has been so dominant throughout his career.

Analyzing Movement Charts

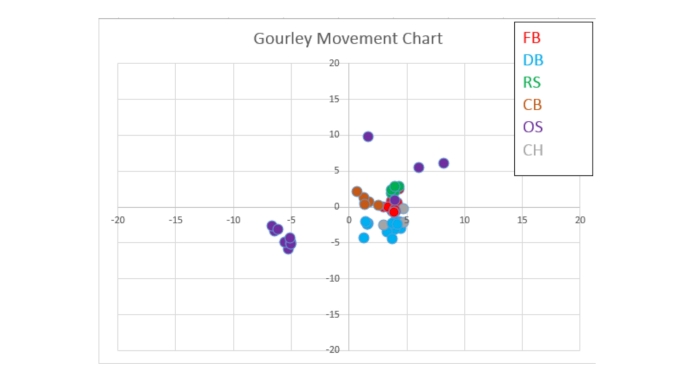

When analyzing a movement chart, the first step is to identify the general shape of the dots. If you look at O’Toole’s movement chart below, you should notice that her fastball and dropball are stacked almost directly underneath her curveball and most of her riseballs. I like to call this pattern a vertically stacked movement combination because she throws two sets of pitches with similar horizontal movements, but with noticeably different vertical movements. This movement combination is very difficult to hit because the hitter has to cover a 10-inch vertical gap despite the pitches only having two inches of horizontal separation.

In between the fastball/dropball and riseball/curveball is her changeup. The changeup is effective because it bridges the vertical gap between her sinking and rising pitches. Typically, when a hitter realizes she has to cover a large gap in movement, vertical or horizontal, she is going to pick between the two extremes. By having a changeup in the middle, it allows O’Toole to have a third option that is similar yet different enough from her other pitches to beat the hitter for a swing and miss. Plus it has a 10 MPH velocity differential which is an optimal swing and miss range for a changeup.

The one negative characteristic of the changeup is that it generates significantly more horizontal break than the rest of her pitches. If she were to develop a changeup that was plotted approximately at the (0, 0) point on the graph, her changeup would be even more deceptive and allow her to have a movement combination similar to Kershaw’s.

Another interesting component of O’Toole’s movement chart is her ability to generate good rise with below average spin rates. When a pitch has backspin and is spinning at a high rate, it creates a force underneath the ball (formally known as Magnus Force) that makes the ball appear as if it is rising.

When the spin rate is lower, that force becomes smaller and gravity takes over, diminishing the rising effect. However, a low-spin pitch can still generate good rise as long as enough of that spin is aligned with the direction of motion (Long, Baseball Prospectus). In other words, O’Toole’s impressive vertical break numbers on her riseball are a result of her ability to spin the ball with near perfect backspin. O’Toole is a perfect example of how spin direction can be more valuable than total spin rate and why an evaluator should never rely solely on spin rate to evaluate a pitch.

O’Toole’s repertoire reminds me of Drew Smyly, a former Tampa Bay Rays starting pitcher currently rehabbing with the Chicago Cubs. Smyly has at best average spin rates and velocity, yet can strike Major League hitters out at an above average rate. Why is this the case? Because Smyly’s pitches, like O’Toole’s, blend well horizontally and have a strong vertical component to them (his fastball generates elite rise on an MLB scale).

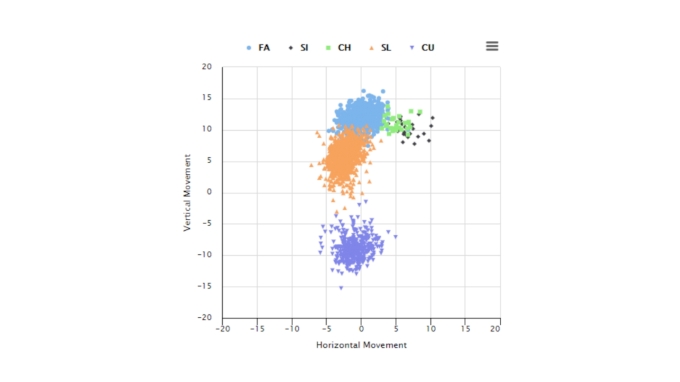

Look at his movement chart above. You should notice that he has four pitches with similar horizontal movements, yet four different vertical movements. Again, this is a very deceptive movement combination, and his strikeout numbers reflect that. Now that you have seen an example of a vertical repertoire, it is time to analyze Delanie Gourley and her horizontal based repertoire.

The first observation you should notice about Gourley’s movement chart is the horizontal shift of the dots. When Gourley throws a pitch, her ball has natural cut spin which causes the ball to break glove-side. It is much more difficult to generate side spin from an underhand thrower than an overhand thrower, therefore, Gourley’s ability to generate significant glove-side break is quite unique.

When we analyzed O’Toole, my first observation noted the vertical separation between her fastball/dropball and riseball/curveball. Gourley has this same characteristic, however, she is not able to generate as much vertical separation between her pitches because she is generating much more horizontal break. Despite this, she is still able to throw three different pitch combinations at three different vertical levels, forcing the hitter to differentiate between the different types of sidespin.

In addition, one of these pitches, her patented changeup, has a 10 MPH velocity differential, making it an ideal swing and miss pitch. Gourley’s movement combination is comparable to Los Angeles Dodgers All-Star closer, Kenley Jansen. The movement chart below shows Jansen is generating extreme cut on his fastball and complementing it with a slider that breaks directly underneath the cut-fastball. Jansen is known for the riding cutter, a pitch that does not possess much depth, has a sharp horizontal break, and high velocity.

Typically, when an overhand thrower throws a pitch with sidespin, it generates some depth. Jansen’s cutter, however, holds its vertical plane and takes a direct right turn (hitter’s view) before it reaches home plate, similar to Gourley’s fastball and riseball (Gourley’s fastball and riseball take a left turn since she’s left-handed). Overall, the hitter has to account for a large amount of vertical and horizontal movement, a difficult combination to handle.

Gourley vs O'Toole

At first glance, Delanie Gourley and Danielle O’Toole seem like they share many commonalities. Both are hard-throwing lefties from Southern California, All-Americans, members of the National Pro Fastpitch league, and currently pitch for Team USA. However, in reality, the way they have achieved this success could not be more different. The overall goal of pitch-tracking data can be summed up in the question, “How can we optimize a pitcher’s effectiveness given her baseline pitch-tracking characteristics?” The biggest challenge with pitch-tracking data will always be implementation.

No two pitchers are the same, and this data proves that a pitcher can accomplish success through many different avenues. Once technology pushes further and further into softball, coaches will have to educate themselves on which movement/spin combinations generate the best results and learn how to find a harmonious relationship between objective and subjective information so they can increase the overall value of their players. After all, the difference between a minor league and major league pitcher is often only a matter of inches, and the same holds true for successful pitchers in softball. If a coach can figure out how to tap into those final few inches, he/she will have a competitive advantage for many years to come.